The Falling Leaf

An imposing blade called Ochiba "The Falling Leaf". It was the cherished sword of a Ronin leader and master swordsman named Kiyokawa Hachirō.

The sword under study was first published on Yuhindo.com by my friend and mentor Darcy Brockbank, and this long form series is dedicated as a tribute to his memory.

Credit to Markus Sesko for research, drafting, review, and translated materials.

Credit to Ted Tenold for photography and review.

The blade was ranked Jūyō-Tōken at the 61st Jūyō Shinsa held on October 20, 2015. In said Shinsa, the blade was attributed to Kashū Sanekage (加州真景). In the past it had been attributed to a different maker, and all that and its provenance shall be given an account of in this article.

The smith Kashū Sanekage

First, the maker, Kashū Sanekage. Sanekage was a swordsmith of Kaga province (which is also referred to as Kashū, hence the name he is usually referred to as). Few signed works of his exist, and even fewer such that are dated, but we do know dated blades from Jōji six (貞治, 1367) and from Ōan five, six, and seven (応安, 1372, 1373, and 1374). Tradition has it that Sanekage had studied with the famous northern smith Saeki Norishige (佐伯則重) from neighboring Etchū province, but as we know dated works by Norishige from eras half a century earlier, that is, from Shōwa (正和, 1312–1317) and Gen’ō (元応, 1319–1321), a direct relationship of the two smiths is today usually ruled out among experts. However, certain similarities in style can be confirmed, as it is the case with other local or nearby smiths, which suggests that some technical exchange had taken place at that time in the northern provinces, or at least that master smiths were aware of the work of their competitors and tried to recreate each other’s approaches.

That said, around the time of Norishige, a new tradition of sword making had emerged in the town of Kamakura, then seat of the Bakufu, the feudal military government of Japan, also referred to as Shōgunate. This tradition was the Sōshū tradition, which had been initiated by swordsmiths from Kyōto and Bizen province who had been invited there, and which was then perfected locally by their students, of which Norishige was one, and Masamune (正宗)—arguably the most famous swordsmith in Japanese history—was another. Their more or less new way of forging and hardening not only turned out to be highly effective in terms of functionality, but also produced activities in the steel based on visible martensite crystals (nie), which had not been seen before in this degree of aesthetic exquisiteness. In the course of the then ongoing campaigns of the Shōgunate, the Sōshū tradition started to spread across the country and quickly gained popularity, and this would be another scenario of why Sanekage may have adopted a style that was similar to Norishige. Today, there are very few remaining zaimei works by Sanekage. One such remaining work is a Jūyō-Bunkazai tanto, described in Honma ‘Kunzan’ Junji’s appraisal dairy (Kanto Hibisho, volume 1):

Tantō, mei: Gashū-jū Sanekage (賀州住真景)

Nagasa 9.5 sun, two mekugi-ana, relatively slender mihaba, sunnobi, thin kasane, mitsu-mune, shallow sori. The kitae is an itame-nagare with plenty of ji-nie and prominent chikei, which tend to nagare. The hamon is a nie-laden notare-chō that is mixed with shimaba, a little bit of gunome, and ara-nie. The bōshi runs out in yakitsume manner on the omote side, and tends to kuzure on the ura side. A bonji and suken are engraved on the omote side, and the ura shows a bonji and incense chopsticks. The nakago has a kaku-mune, some niku on the cutting edge side, and katte-sagari yasurime. The signature is executed in a smallish manner with a thin chisel and is basically a match with the mei of the work of Sanekage (真景) that has been designated as a Jūyō-Bunkazai. Among all works of the first and second generation Sanekage that I have seen, this blade displays the jiba that is most similar to Norishige (則重). From a chronological point of view, a direct master-student relationship between Norishige and Sanekage cannot be confirmed, but it is known that the first generation Sanekage did continue Norishige’s style quite faithfully, and the blade introduced here can be regarded as supporting evidence for this tradition

Extract from Honma Junji’s Kanto Hibisho

In Kantei, Sanekage is the best answer for blades that fall between Norishige and Tametsugu on the quality spectrum. The key trait to look for is a jihada executed in itame featuring vividly standing out hada (hadadachi-gokoro) with dark rings (chickei) among strong nie that resembles Norishige’s famed Matsukawa hada but is slightly inferior.

This excerpt from the Honma Junji’s kanto Hibisho vol. 4 illustrates the point:

The prominent chikei and kinsuji speak for the Sōshū tradition, but the jiba is rather dark, whereupon I judge it as a Hokkoku-mono and would attribute it to Norishige (則重) at first glance. However, also Sanekage (真景) or Tametsugu (為継) come to mind, but from the point of skill of its maker, I think it ranks above of Tametsugu, and therefore I am eventually nailing down my attribution to Sanekage

Sanekage is first and foremost best understood as a quality appraisal asserting that the work is “one step down from Norishige”. It is not a high-confidence judgement on the specific identity of the smith, even if the judgement is unanimous and all the traits attributed to Sanekage are carried into the work. To understand this, it’s important to know that through the Muromachi and Edo period there is a kind of void of sources describing the Hokkoku-mono smiths of the Nanbokucho period. And for good reasons, these times were chaotic with the fall of the Kamakura Shogunate, and the Northern provinces were considered backwater compared to the refined imperial city of Kyoto or the ancestral Bizen forges along the Yoshi river. There are many mysteries left, for example, we know of another obscure mastersmith whose work is noted as indiscernible from Norishige in his Matsukawa style. His name is Hata Chogi, and he left behind only 3 signed tanto, with one dated 1356. Today, Hata Chogi is not a good kantei answer, as no mumei work is attributed to him. Further complicating matters, there are no recorded Honami appraisals to Sanekage, so we can’t rely on old appraisals by reputed judges such as Hon’ami Kochu or Kojo to reconstruct their perception of Sanekage. At the NBHTK, Sanekage as an attribution appears first at the Jūyō session 11 and Tametsugu appears first Jūyō session 12. With this context in place, we understand that there is some quite a bit of wiggle room as to who might have made it in the end.

Sanekage is not a common attribution either, and in the current records of the NBHTK and the Ministry of Culture, Sanekage has just 46 swords ranked Jūyō-tōken (28 Katana, 8 Wakizashi, and 10 Tanto), one ranked Tokubetsu Jūyō that has been re-attributed to Go Yoshihiro, and the aforementioned Juyo Bunkazai tanto. The fact that there are no Tokubetsu Jūyō works by Sanekage (Or Tametsugu, for that matter), highlights once more that these attributions are points along a quality gradient. By comparison, Norishige has 115 Jūyō-tōken (amongst which, 27 Tokubetsu Jūyō), and Tametsugu has 78.

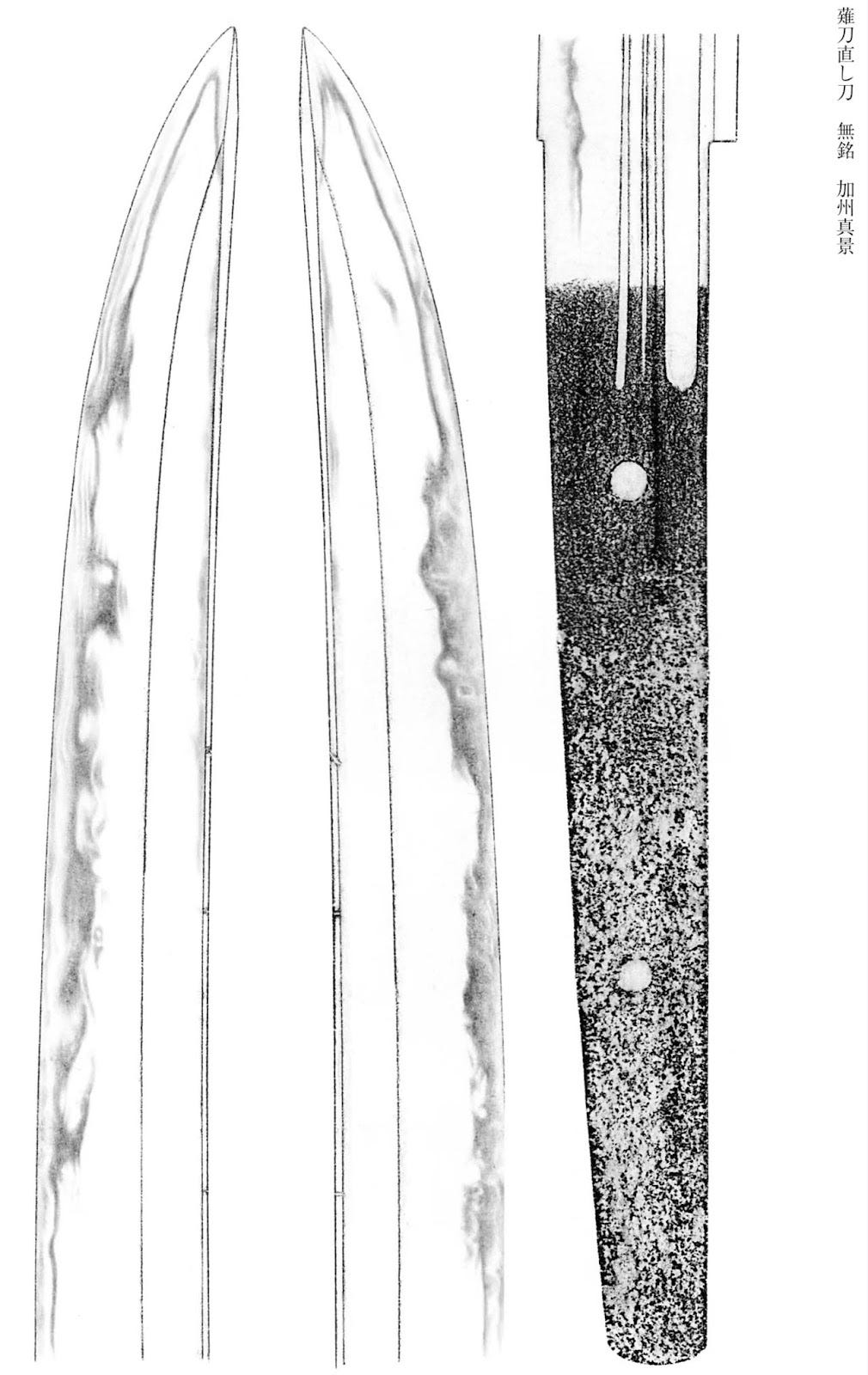

The Naginata Naoshi Katana

The blade is what is referred to as a naginata-naoshi (薙刀直), a naginata halberd, which was reworked (Japanese: naosu) into a different type of sword, in this case, into a katana (刀). The polearm type of the naginata emerged in the Heian period (794–1185). As early as by the end of this period and the then occuring Genpei War, high-ranking warriors recognized the efficacy of the naginata and made it their weapon of choice when fighting on foot. Accordingly, famous figures of that time period being recorded as fighting preferably with the naginata have become a fixture of Japanese lore, e.g., Minamoto no Tsunemitsu (源経光, died 1146), the warrior monk Benkei (弁慶, 1155–1189), female warrior Tomoe-Gozen (巴御前, late 12th century).

The naginata being wielded by lower ranking soldiers against the horses of mounted warriors, for example, and being a weapon of choice by higher-ranking warriors when fighting on foot remained the same throughout the Nanbokuchō era (1336–1392), a period of Japanese history that experienced once again an increasing number of battles, this time caused by the conflict between the Northern and Southern Courts, both pretenders to the throne of Japan. During this time period, we see a significant increase in the production of fine naginata, and Bizen being on the forefront of purveying weapons of this type and quality to the highest-ranking warriors. Unlike Yari, which were considered disposable and - with rare exceptions - were of lower quality, many extant Naginata reflect the level of forging and quality materials that smiths employed to forge Tachi.

By the end of the Muromachi period, and entering the Momoyama era, changes in the way battles were fought and significant changes among the warrior class itself took place. That is, this was the time when Samurai took over land ownership on a large scale and were no longer more or less armed guardians of someone else’s land as they had been in previous periods. As a result, local Samurai rulers now also had to administer the lands under their rule, which was of course not done in full armor wearing a tachi, but in a “civilian Samurai attire” so to speak wearing the iconic daishō pair of swords consisting of a katana and a wakizashi. In other words, was the sword worn to civilian or casual attire earlier mostly for reasons of self-defense, it had now become the visible symbol of rank and authoritative power, and eventually the status symbol of the entire warrior class per se.

The Shōgun, the Daimyō, and highest ranking Samurai were of course seeking to wear the best blades possible. As the qualitative and aesthetic zenith of Japanese sword making is often considered to have been the Kamakura and Nanbokuchō periods by connoisseurs and experts alike, this of course means that the body of work to select from was tachi, tantō, and naginata, the latter two not suitable for being worn as a katana, that is, as the longer and more prestigious part of the daishō pair.

However, there is a “workaround” for this problem: As it is widely known, tachi were often shortened to a length practically appropriate for being mounted as a katana. In case of a naginata polearm, the tang was shortened as well, and the bulbous tip section had to be reduced to achieve the blade proportions of a katana. As naginata were mostly designed to be durable and highly effective cutters on the battlefield, their “efficacy” remained unchanged when being shortened to wear them as a katana. Accordingly, the following saying developed among warriors: Naginata-naoshi ni namakura nashi (薙刀直しに鈍刀なし) – “No sword made from a naginata is dull!”

When warlords like Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi built up their extensive sword collections towards the end of the sixteenth century, they created another momentum in the movement of swords being regarded as works of art. Swords being worn by the upper echelons of the warrior class were now also regarded as conversation starters and objects of discussions in the sense of who is wearing what. Also, the increasing production of publications via woodblock printing in the early Edo period resulted in the first publicly available sword-related titles and an ever growing sophistication of the qualitative rankings of swordsmiths.

In a nutshell, many Samurai from the end of the Muromachi and the subsequent Momoyama period wanted to actively wear the best blades in their possession. Thus, reworking a naginata, if it was one’s best blade, into a katana was not considered a sacrilege per se, but was understood as making it become a part of one’s life rather than having it sit in a treasury or storehouse. And with the aforementioned publications and rankings, presenting and receiving a gift of a blade made by a smith renowned for having produced the finest examples of its type was very much desired.

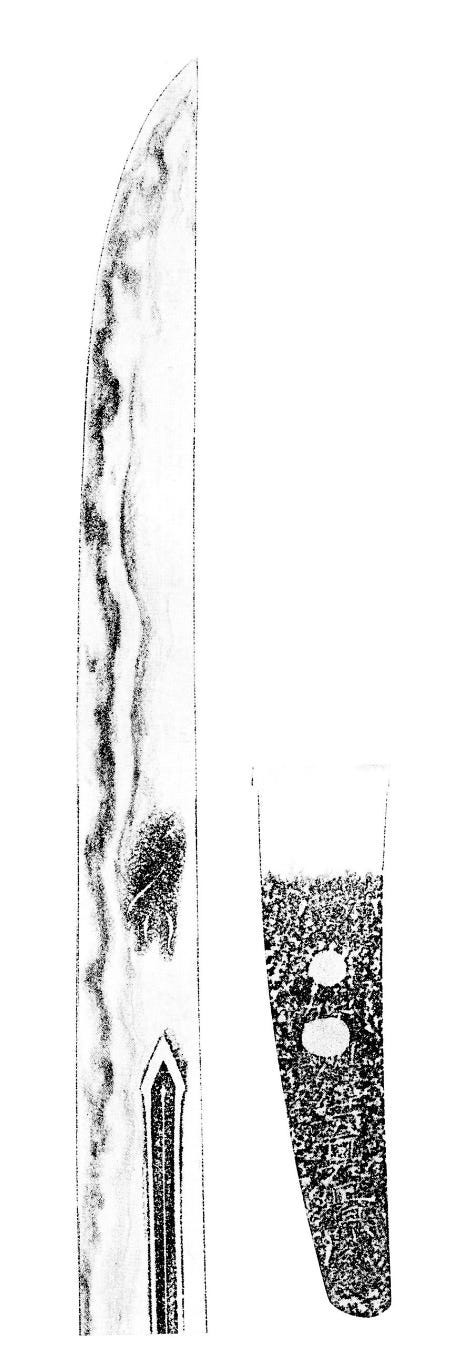

The Naginata Naoshi Katana attributed to Kashū Sanekage

The naginata-naoshi katana in question, however, is a rare case where only minimal alterations have been carried out. That is, it preserves parts of its original tang, its ha-machi and mune-machi notches were only moved up slightly by ~5cm, and there is still a kaeri in the bōshi and ample hardening in its turnback along the mune. Apart from that, the hamon remains wide in the monouchi, the striking area of the blade before the tip, and therefore we can conclude that apart from some shortening, the original shape of the blade was pretty much preserved in its initial form, which is very rare for polearms of this time period. Out of 28 Katana presently attributed to Sanekage at Jūyō, 4 are naginata-naoshi. Amongst these four, the present blade is the only extant work with an unaltered kissaki. With an imposing 75.2 cm nagasa, 2.6 cm of sori, and a robust 1.1 cm kasane that tapers along the blade, the sword has a powerful presence. It is remarkably wide, with a motohaba of 3.3 cm. Weighing in at an impressive 985 grams, there can be no doubt that it was meant for use by someone of formidable strength.

Credit for the photography to Ted Tenolds and Darcy Brockbank. The HD version can be downloaded here

Impressions

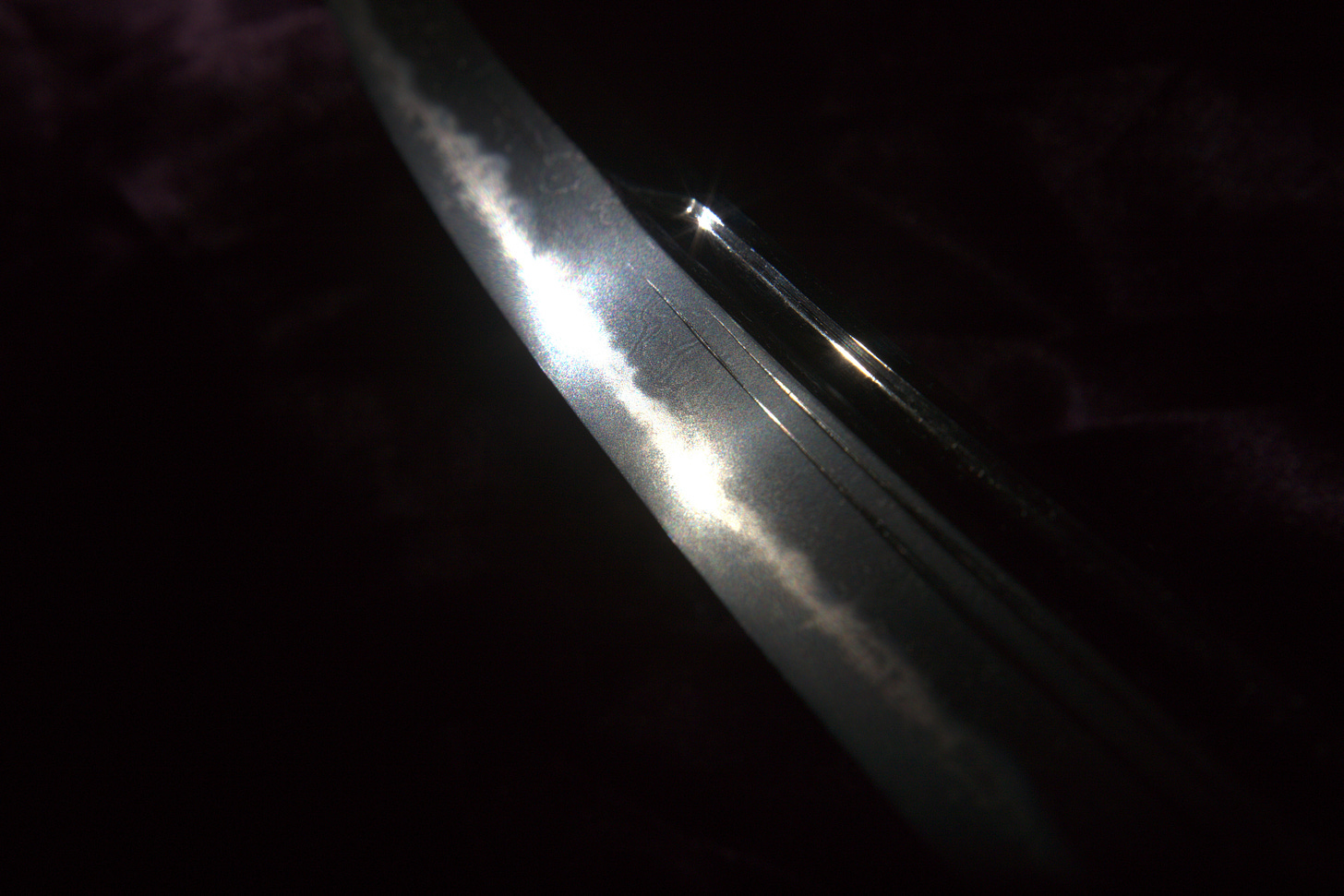

The sword’s hamon begins with a thick nioiguchi and relatively sparse nie interwoven into the ha, before rising in flamboyance in a spectacular manner at the monouchi. There, the quality and variety of the nie reaches its apex, and it takes on an icy quality that is so typical of Sōshū-Jōko (the name given to the great early masters of the Sōshū tradition). This crescendo deliberately reflects an intention by the smith to reinforce the lifespan of the ‘business end’ of the blade when faced with damage without sacrificing its resilience to the brutal shocks expected of polearms clashing in battle against cavalry.

The blade begins with a thick nioiguchi under a finely carved Naginata horimono. Dark rings of chickei appear in the ji.

At the monouchi, the edge takes on a frosty quality from the abundant layers of nie. This frosted appearance is a hallmark Soshu-den excellence.

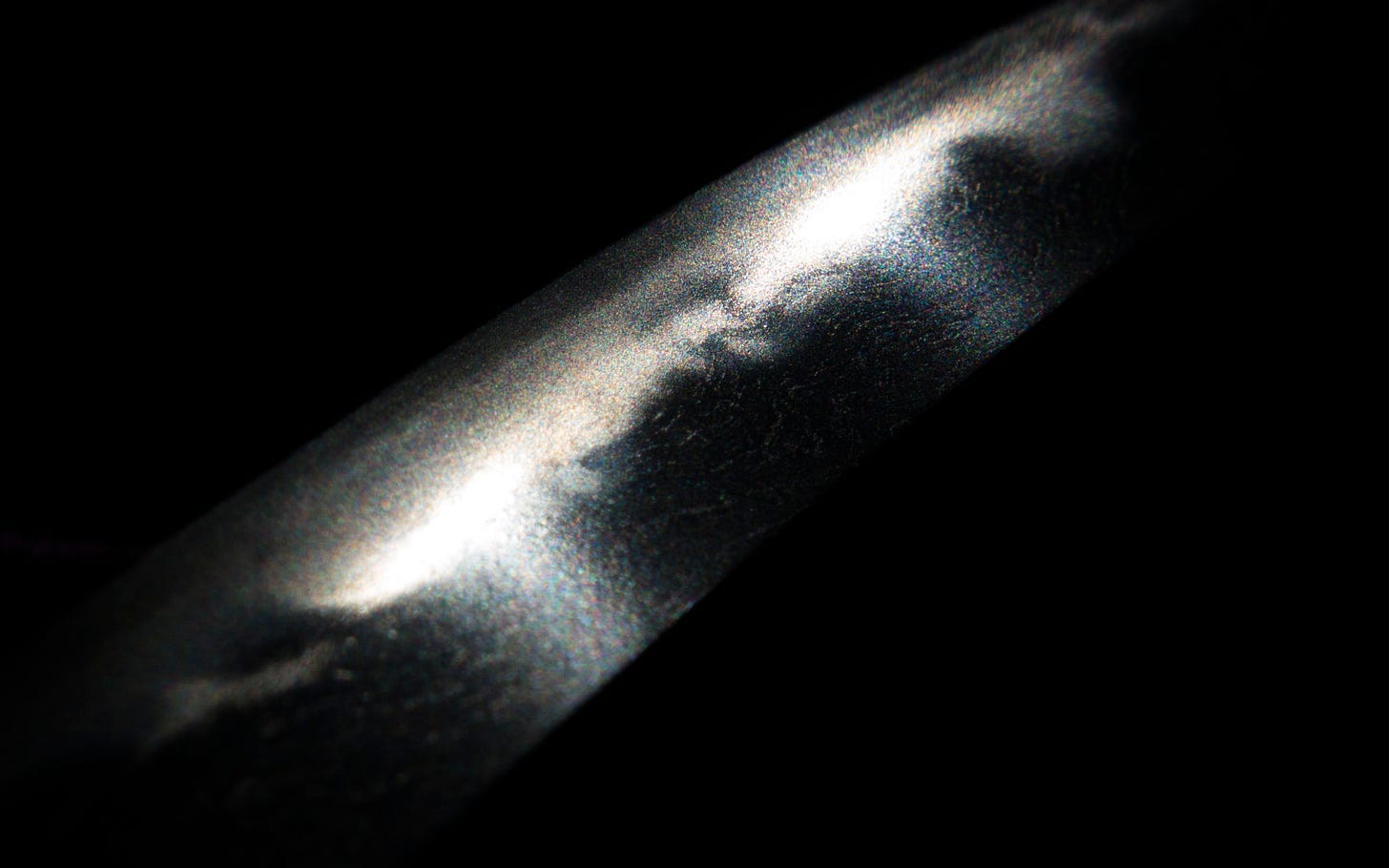

Nie forming overlapping waves.

The jihada is rich in thick streaks of jinie (white lines) and chickei (dark rings) arranged in matsukawa (pinebark).

Kashū Sanekage

Jūyō-tōken at the 61st jūyō shinsa held on October 20, 2015

naginata-naoshi katana, mumei: Kashū Sanekage (加州真景)

Measurements: nagasa 75.2 cm, sori 2.6 cm, motohaba 3.3 cm, nakago-nagasa 22.6 cm, nakago-sori 0,2 cm

Description

Keijo: naginata-naoshi-zukuri, iori-mune, wide mihaba, no widening towards the tip, thick kasane, high shinogi that makes the shinogi-ji drop off towards the mune, deep sori

Kitae: standing-out itame that is mixed with mokume and nagare, in addition plenty of ji-nie and fine chikei, the steel is blackish

Hamon: notare-chō in nie-dek that is mixed gunome, togariba, and yahazu-ba along the bottom half and along the monouchi, also ara-nie appear in places and there are hotsure, yubashiri, nijūba, tobiyaki, kinsuji, and sunagashi

Bōshi: shallow notare-komi with a pointed kaeri

Horimono: on both sides a naginta-hi with futasuji-hi which end in marudome

Nakago: ō-suriage, kurijiri, kiri-yasurime, two mekugi-ana, mumei

Explanation

It is said that Kashū Sanekage (加州真景) was a student of Etchū Norishige (越中則重). As we know dated work from Norishige from the eras Shōwa (正和, 1312-1317) and Gen'ō (元応, 1319-1321) and from Sanekage from the noticeably later Jōji era (貞治, 1362-1368), it seems that Sanekage was not a direct student of Norishige but was rather influenced by his style indirectly. This blade shows a standing-out itame that is mixed with mokume and nagare and that features plenty of ji-nie and fine chikei. The steel is blackish and the hamon is a notare-chō in nie-deki that is mixed with gunome, togariba, and yahazu-ba, and when we combine this with the abundance of hataraki along the habuchi, we recognize the typical characteristics of Kashū Sanekage. Therefore, the attribution to this smith was achieved unanimously. Both ji and ha are nie-laden and in particular the abundance of variety along the habuchi is not only very impressive but also excellently executed.

The old attribution to Sōshū Sadamune

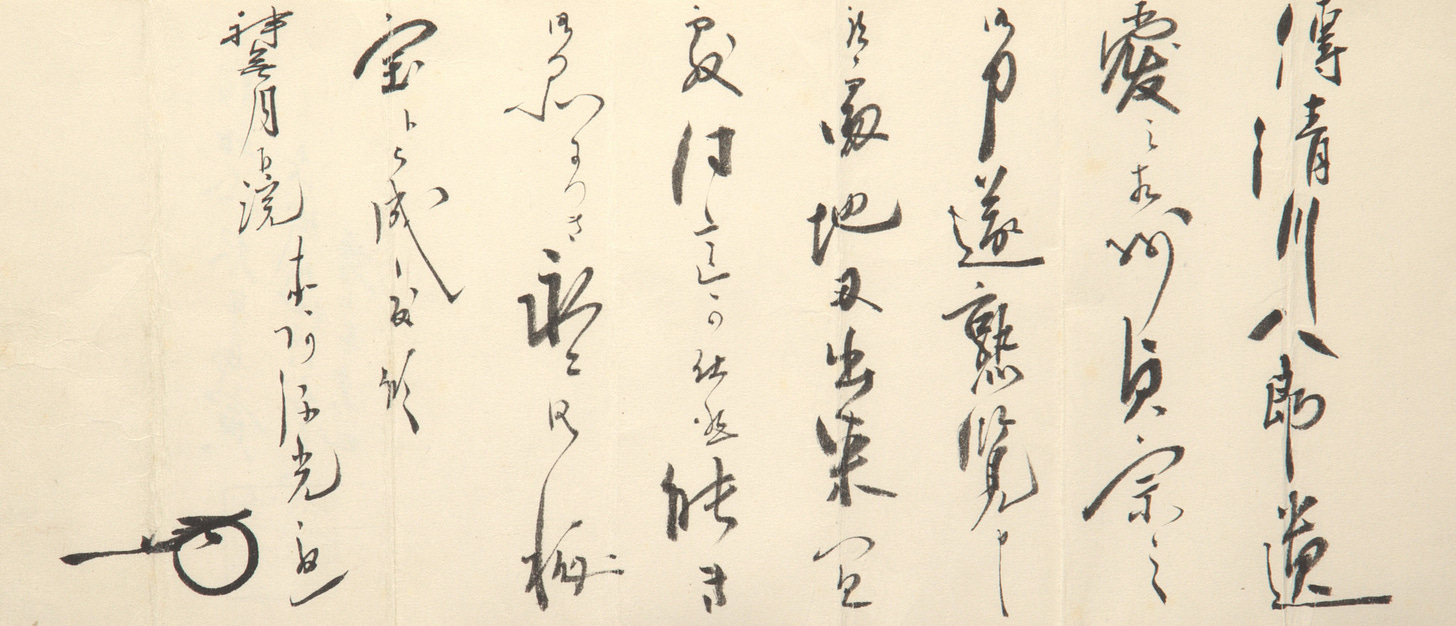

The reattribution of a blade from Sanekage at jūyō to Go Yoshihiro at Tokuju highlights that the boundaries between Sanekage and the Sōshū masters can be fluid in rare cases. In the late Edo period, the state of scholarship was not as advanced as today and judgements were often “looser” owing to economic and social pressure that we will explore in later articles. For example, many swords reattributed to Shizu by the NBHTK once held an attribution to Masamune during this period of ‘loose’ judgements. In the same vein, the blade under study had been traditionally attributed to Sadamune (貞宗), a student of Masamune who was later adopted by his master. We do not know since when the blade was handed down as a work of Sadamune, but said fact was recorded so by Hon’ami Kōson (本阿弥光遜, 1879–1955), who was a member of the renowned Hon’ami family of sword polishers and appraisers to the Shōgun and a vital figure in the transitional time from traditional to modern scholarship in this field. In an accompanying note (soejō, 添状) to the blade from 1913, he wrote:

Den Kiyokawa Hachirō iai no Sōshū Sadamune kore, o-katana tsui ni jukuran mōshisōrō dokoro jiba deki yoroshiku dōi no tsukamatsurubeku sōrō yoki, o-shina nitsuki nagai go-hihō to nasaretaku sōrō.

Kannazuki gekan – Hon’ami Kōson + kaō

“This Sōshū Sadamune is said to have been cherished by Kiyokawa Hachirō. Upon carefully examining the blade, I want to point out that its jiba is of an excellent deki and that I respectfully agree with its period attribution to Sadamune. A fine work, which should be treasured for perpetuity.

In the last third of October, Hon'ami Kōson + monogram”

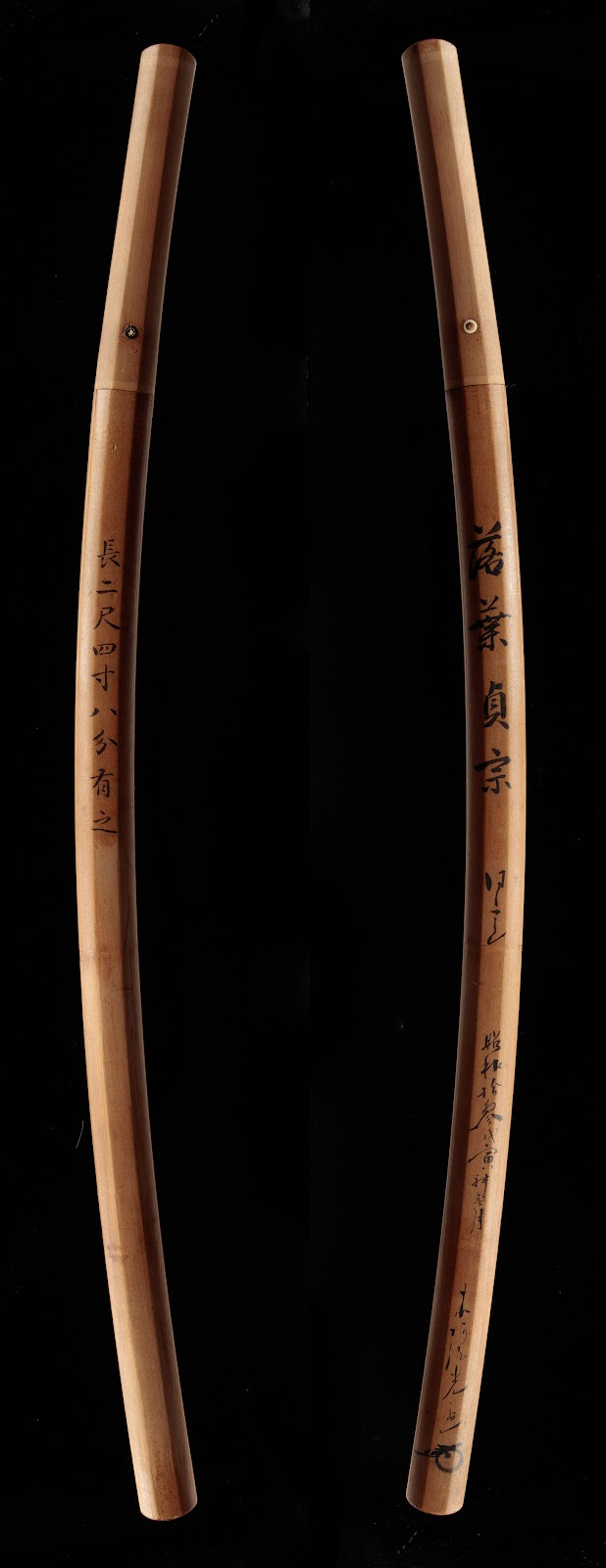

The blade comes with his old sayagaki, made at the same time as the origami was issued. The sayagaki states:

Ochiba-Sadamune

Dōi Shōwa jūsan tsuchinoe-tora kannazuki Hon'ami Kōson + kaō Nagasa 2 shaku 4 sun 8 bu kore ari

Ochiba-Sadamune. In agreement, October of Shōwa 13 (1938), year of the tiger Hon'ami Kōson + kaō Nagasa 75.2 cm

Who was Kiyokawa Hachirō?

Kiyokawa Hachirō (清川八郎, 1830–1863) was quite a figure in the turbulent times that ushered in the end of the Tokugawa regime and the feudal system. Kiyokawa was born as the eldest son of Saitō Hidetoshi (齋藤豪寿, born 1810) in Shōnai in Dewa province (present-day Yamagata Prefecture). Hidetoshi was not only a Gōshi (郷士), a Samurai living in the countryside tasked with administering a village, thus allowed to wear a sword, but also a fairly wealthy sake brewer, and Kiyokawa’s mother, Kiyo (亀代), was coming from money as well, that is, from the wealthy merchant family Mitsui (三井) from Tsuruoka. Aside from running his sake business, Hidetoshi was also a man of culture well versed in history, literature, poetry, and calligraphy, and also had a keen interest in swords. At age ten, Kiyokawa, then named Saitō Genji (斎藤元司), began learning from local scholars, but was eventually expelled for misbehaving. Kiyokawa then received his first training in swordsmanship at the age of 17 from local swordsman Itō Yatōji (伊藤弥藤治), and was also taught in the same year by Fujimoto Tesseki (藤本鉄石, 1816–1863), who had stayed in Kiyokawa and who later became a leader of the pro-Emperor Tenchūgumi (天誅組) group of Samurai and Rōnin. It is believed that it was this encounter with Tesseki that ignited in the teenager Genji a desire to study in Edo, which he put into action a year later.

Portrait of Kiyokawa Hachirō

In parallel to his academic pursuits, Kiyokawa passionately trained in swordsmanship in Edo, entering the Genbukan (玄武館) Dōjō in Kaei four (嘉永, 1851), where he learned the Hokushin Ittō-Ryū (北辰一刀流) school of swordsmanship directly from its founder, Chiba Shūsaku (千葉周作, ca. 1794–1856). Nine years later, he received his “license of total transmission” of the school's teachings, meaning that he was now officially allowed to teach himself, which he did in his own Kiyokawa School. Incidentally, Kiyokawa had taken a nine-months break from teaching and training in Ansei two (1855) to travel the country extensively with his parents, meeting with notable persons from all corners of the Honshū region.

After the Sakuradamon Incident (桜田門外の変) of 1860, in which Chief Minister of the Shōgunate Ii Naosuke (井伊直弼, 1815–1860) was assassinated by Rōnin who were against his proposals of opening the country to the West, pro-Emperor and anti-foreign, Samurai and Rōnin started to regularly meet at the Kiyokawa School to discuss how to best protect the country. One month prior to said incident, Kiyokawa had founded the Torao no Kai (虎尾の会), “Tiger Tail Association,” and installed himself as its leader. It is said that the background for the naming was Kiyokawa's take that he was not even afraid to step on a tiger’s tail in order to protect his country. The Torao no Kai Association had 15 members, one of which being the famous swordsman Yamaoka Tesshū (山岡鉄舟, 1836–1888).

As members of the Torao no Kai were allegedly part of the 1861 assassination of Dutch-American interpreter Henry Heusken (1832–1861), and for other reasons, the Shōgunate made arrests accordingly, disbanded the association, and even imprisoned Kiyokawa's wife O-Ren (お蓮) and his younger brother Kumasaburō (熊三郎). Kiyokawa then lived on the run, but continued his movement of overthrowing the Shōgunagte, mostly from Kyōto. His hope was that the also anti-Tokugawa Satsuma Domain would lead its troops to the old capital to join his movement, but he did not receive any commitment from their officials. After returning to Edo, Kiyokawa submitted a petition to Matsudaira Shungaku (松平春嶽, 1828–1890), then a chief politician of the Shōgunate, which included three “emergency measures:” 1. The expulsion of all foreigners, 2. General Amnesty for men of his and similar movements that had been imprisoned, and 3. Fostering men to excel both in literature and martial arts.

Shungaku accepted the petition and pardoned the imprisoned Torao no Kai members, although Kiyokawa was deeply saddened when he learned that his wife O-Ren had already died in prison. Shungaku also granted the formation of the Rōshigumi (浪士組) group of 234 Rōnin lead by Kiyokawa, who had tricked him by claiming it was for the protection of the Shōgun in Kyōto. Having now gathered men for his own hidden agenda, among them, for example, famous figures like Kondō Isami (近藤勇, 1834–1868) and Hijikata Toshizō (土方歳三, 1835–1869), Kiyokawa ordered the group in Bunkyū three (文久, 1863) to proceed from Edo to Kyōto on the occasion of Shōgun Tokugawa Iemochi’s (徳川家茂, 1846–1866) visit of the old capital to meet with Emperor Kōmei (孝明天皇, 1831–1867).

Upon the arrival of the Rōshingumi, however, Kiyokawa’s scheme of shifting protection from the Shōgun to the Emperor had been revealed, and so he immediately commanded the group to return to Edo, a move that led to its disbanding. A smaller group of dissenting members remained in Kyōto, where they formed a few months later the famous Shinsengumi (新撰組) that once again served the purpose of the Shōgun.

By then, the Shōgunate had infiltrated the remaining Rōshingumi members with spies and had sent out six assassins to kill Kiyokawa, which they successfully did on the 13th day of the fourth lunar month of Bunkyū three (1863) at the Akabane Bridge (赤羽橋) in the Azabu District of Edo. According to the Japanese way of counting years of life, as indicated earlier, Kiyokawa Hachirō was 34 years old when he was assassinated.

Akabane Bridge and Suiten Shrine (Akabane Suitengū), from the series Famous Places in Edo (Edo meisho)

It is said that Rōnin and Torao no Kai member Ishizaka Shūzō (石坂周造, 1832–1903) recovered Kiyokawa's head, which was subsequently kept by Yamaoka Tesshū’s wife Eiko (英子) (Ishizaka’s wife was Eiko’s sister). The head was eventually returned to Kiyokawa's family when his surviving younger brother Kumasaburō had his body reburied in the Saitō family gravesite of the Kanki-ji (歓喜寺), a temple in Kiyokawa in Shōnai. However, the initial grave of Kiyokawa at the Dentsū’in (伝通院) in Edo (present-day Bunkyo Ward of Tōkyō) was preserved and exists to this day.

The Mounting of the Ochiba

The mounting of the Ochiba is every bit as fascinating as the Ochiba blade. First, its scabbard (saya) is covered in wrinkled leather (shibogawa), which was patterned to resemble bamboo, an interpretation that is extremely rarely seen. Also rare is the fact that the craftsman left his name fairly prominently embossed at the top of the scabbard: Isaburō Motoie (伊三郎基家). Unfortunately, the maker and his school or workshop could not yet be identified, although this is often the case with scabbard makers and lacquer artists, etc., as only few records of their names and lineages were compiled. The iron fittings, delicately highlighted with gold, follow the tree theme of the scabbard, with the hilt ornaments (menuki) depicting snails on pieces of old wood with some tendrils, and the tsuba depicting an oak tree.

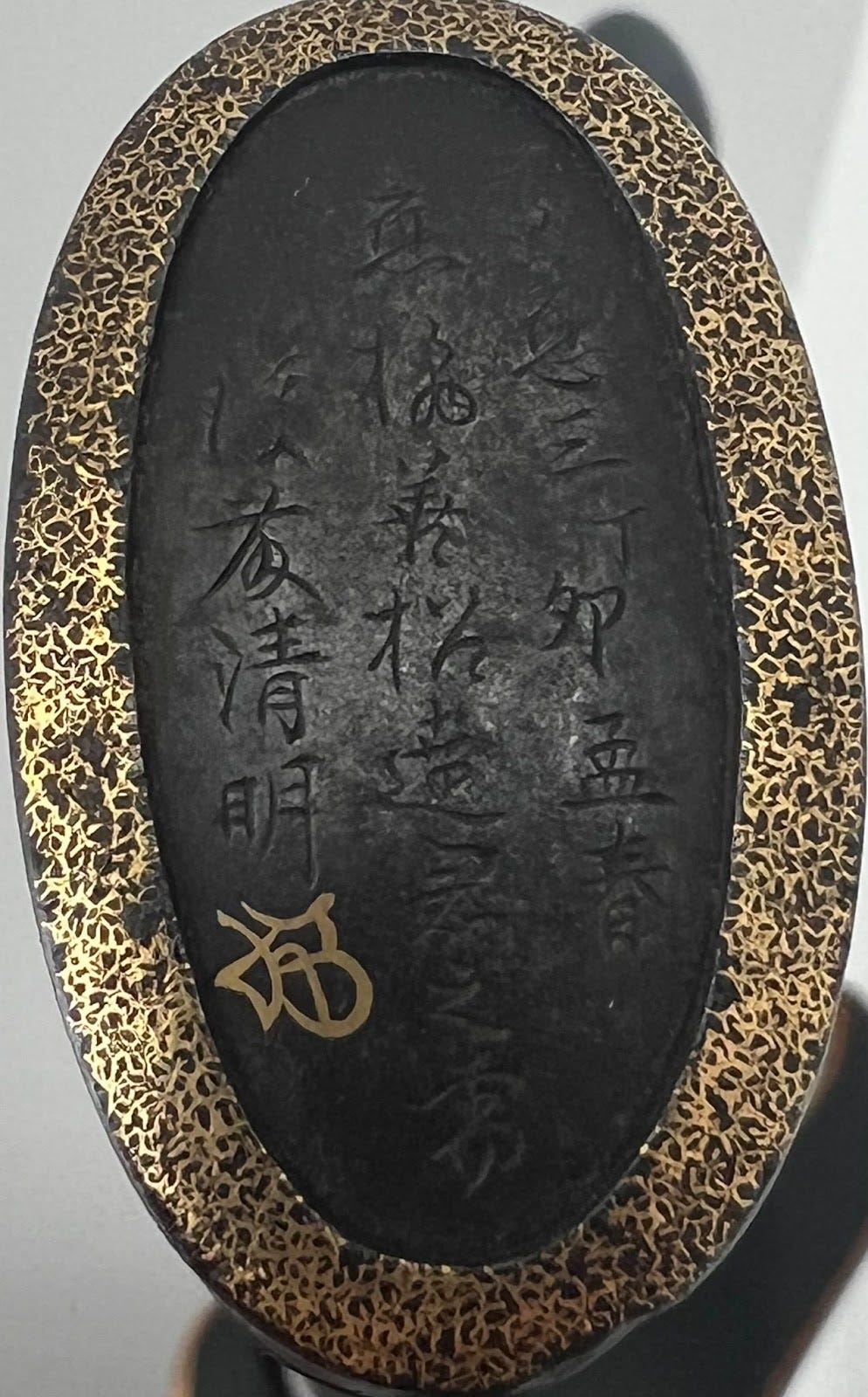

The maker of the fittings, Gotō Kiyoaki (後藤清明, born 1815, recorded until 1868), is said to have studied with the sixth generation Gotō Seijō (後藤清乗, 1801–1836) in Edo. Although having been allowed to use the renowned Gotō name, Kiyoaki was not related to the famous Gotō family of sword fittings makers, who were purveyors to the Shōgunate since the end of the 15th century. We do not know Kiyoaki’s real family name, only his first name, Einosuke (栄之助), and that he also used the art name (gō) Shūzuiken (秀瑞軒). Apart from that, we know that Kiyoaki lived in the Otamagaike (お⽟ヶ池) neighborhood of Edo (present-day Kanda District). Incidentally, a koshirae featuring fittings by Kiyoaki has passed Jūyō in the 37th Jūyō Shinsa held in 1991 (shown on next page). It is of a similar Bakumatsu era style in terms of hilt wrapping and taller than usual fittings, e.g., kashira, fuchi, and kojiri.

Kiyoaki’s signature and date is engraved on the kojiri of the saya as follows:

慶應三丁卯孟春 應橘善松逹君之需 後藤清明「花押」

The name of the client, however, leaves some room for speculation. The name is composed of four characters, which is the most common variant, that is, two characters for the family name, and two characters for the legal first name. However, it appears that the name in question is comprised of one character for the family (or clan) name, Tachibana, two for the first name, Yoshimatsu, and one for the legal first name, Satoshi, with the character for the latter leaving several more reading options. An online search of numerous combinations and omissions of the characters for said name have not yielded any results. As the fittings were made four years after Kiyokawa’s death, the koshirae was commissioned by the person who held Kiyokawa’s sword in his possession following his assassination, possibly one of his associates or relatives. Apart from ongoing research on the craftsman Isaburō and the person who commissioned the fittings, and likely the entire koshirae, another extremely rare aspect of this mounting is the fact that it was designed to be worn on the right side of the wearer. That is, the kurigata, to which the sageo cord is tied, is positioned on the opposite side than usual, and the hilt wrapping and position of the menuki follow the approach used for a sword worn on the right side. Thus, it must be assumed that the wearer was either left handed, or was faced with an incapacity that made it impossible to use or draw the sword with his right hand from the standard left position in the sash.

Cases like this do exist, but are very rare, as indicated. One recorded case would be that of Kawaji Toshiakira (川路聖謨, 1801–1868), first Governor of Nara, later Finance Magistrate and Foreign Affairs Magistrate of the Shōgunate, and cosigner of the Treaty of Shimoda between Japan and Russia that opened Japanese ports for Russian ships. However, Kawaji had to retire shortly after his appointment due to an illness, and his health seems to have declined from there as soon thereafter, Kawaji suffered from a stroke that lead to a paralysis of the right side of his body. When the Shōgunate fell in 1868, Kawaji followed the Samurai code and committed honor suicide. Due to his paralysis, however, he felt incapable of properly accomplishing the traditional seppuku method of cutting into his abdomen with his sword, and therefore shot himself in the neck with a pistol. The portrait of Kawaji Toshiakira shown below was taken after his stroke as one can see that he is wearing his short sword (wakizashi) on the right, his paralyzed side, to be able to draw it with his functioning left hand.

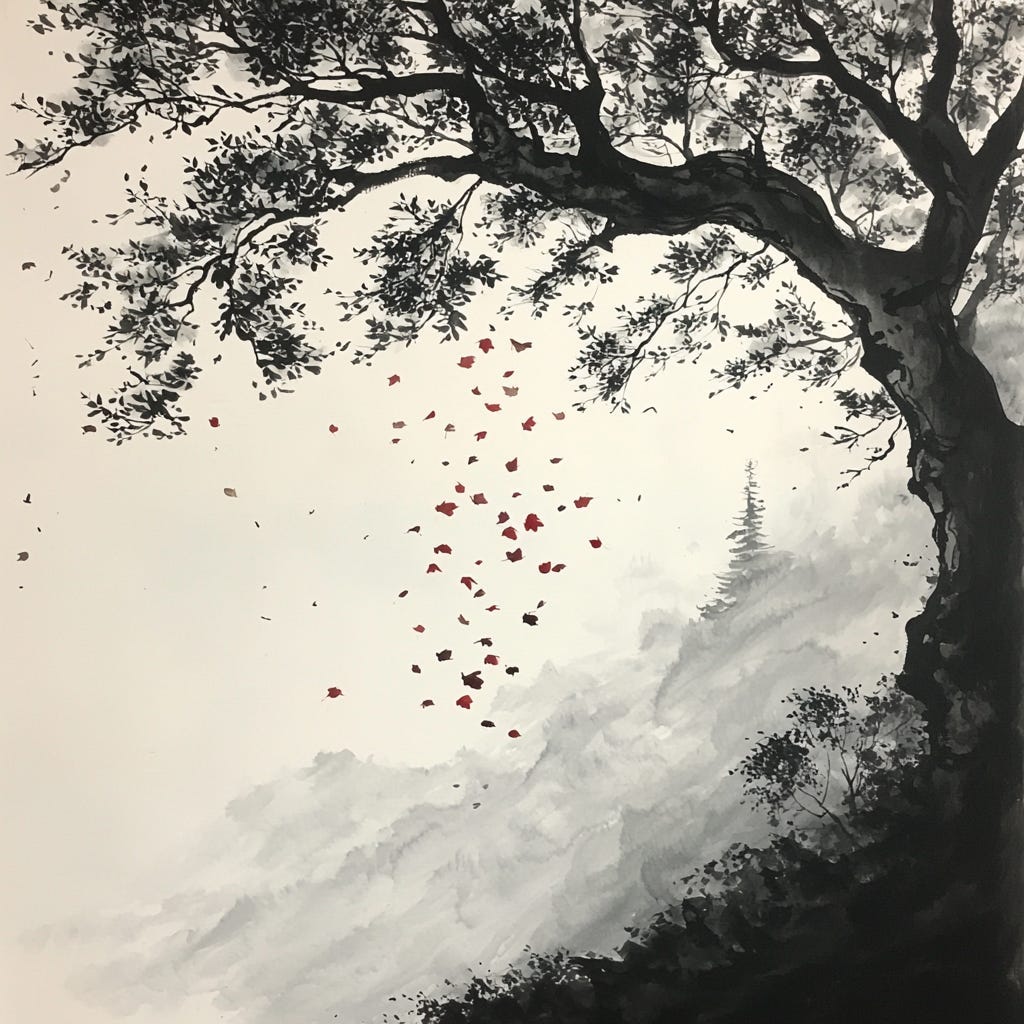

The origins of the name Ochiba

Not only did Hon'ami Kōson record its provenance, but also its name, Ochiba-Sadamune (落葉貞宗), which he recorded via a sayagaki on the shirasaya of the blade. Before this name is addressed, it should be pointed out that the blade bears nine kirikomi, nicks caused by contact with another edged weapon, which is a truly impressive amount by any measure in the field of Nihonto. The sword has experienced intense fighting, which supports the provenance to master swordsman Kiyokawa Hachirō who was engaged in numerous fights and duels.

Ochiba-Sadamune, or now rather Ochiba Sanekage, as sword knowledge has significantly improved since when Kōson examined the blade in 1913, leading to a more precise attribution to a different, but related smith.

Ochiba means literally “falling leaf” or “falling leaves.” Swords were often named after their owner, e.g., the Ishida-Masamune (石田正宗), named after it having once been worn by Ishida Mitsunari (石田三成, 1560–1600), or after unique visual features e, e.g., the Atsushi-Tōshirō (厚藤四郎), a prominently thick (Japanese: atsushi) tantō by Tōshirō Yoshimitsu (藤四郎吉光). Another and quite common form of naming was referencing the cutting ability of a sword, for example, the Kotegiri-Masamune (籠手切正宗), named after having cut (Japanese: kiri) through the kote sleeves of an armor. However, there were also more poetical ways to do so, e.g., Sasanoyuki (笹雪), lit. “snow on a bamboo leaf,” alluding to no force being needed to cut with such a blade as it will cut so effortlessly like snow gliding from a bamboo leaf.

The Ochiba seems to fall into the latter category, a poetic reference to its cutting ability, that is, the blade cutting as effortlessly as the leaves falling off trees in a breeze in autumn. However, there is another possible background for this naming. Ochiba is also the name of a sword in the Nansō Satomi Hakkenden (南総里見八犬伝, The Chronicles of Nansō Satomi’s Eight Dogs), an epic novel originally published over the course of twenty-eight years between 1814 and 1842. Set in the Muromachi period, the story follows the adventures and mishaps of eight fictional warriors, who gradually discover their shared origins as “spirit-children” of a Satomi princess and unite in Nansō as loyal defenders of her clan. Consisting of a total of 106 booklets, the Nansō Satomi Hakkenden is considered the largest novel in the history of Japanese literature. Although only a limited number of copies of the booklets themselves were printed, the tale was retold through various mediums, including oration and live performance, leading to its popularity among many social classes at the time. Also Kabuki plays based on it were often performed, leading to ukiyo-e depicting their actors playing the roles of the eight warriors.

The story takes place in Kanshō six (寛正, 1463). A warrior named Aihara Tanenori (粟飯原胤度) proceeds to Kamakura, where he purchases two swords, the Ochiba and the Ozasa (小篠), which he then presents to his lord, Chiba Yoritane (千葉自胤). The Ozasa, lit. “small bamboo leaves,” was named this way as the fuchi of its hilt was decorated with snow-covered bamboo leaves. The Ochiba, in turn, got its name from a much more dramatic background, which was the knowledge that when you cut with it, the leaves would fall from the trees even when it was not autumn.

It is fascinating to think that this popular series of novels may have had a profound influence on shaping the young Kiyokawa Hachirō. After all, the epic tells the classic story of the hero discovering his grand destiny and embarking on a grand quest to face villains of formidable power. The Nansō Satomi Hakkenden’s influence on popular culture has been significant. It is credited for having inspired popular manga such as Dragon Ball Z and many JRPG, and it may as well have inspired Kiyokawa Hachirō and other Ronin to embrace the call of adventure.

Taking into consideration the name of the blade, it is conceivable that the scabbard emulating bamboo is a reference to the Ozasa counterpart of the Ochiba, forming a complete set based on the epic Nansō Satomi Hakkenden. References like this, the more subtle, the better, aiming at those with a profound understanding of the context the artist tries to convey, are a common trait found in Japanese art.

It is thus possible that the Ochiba name of the blade in question was not coined because it cuts so effortlessly like leaves falling off trees in a breeze in autumn, but as a reference to said story, meaning that the blade cuts so powerfully that it makes leaves fall off from trees…